"If I run it, they will learn."

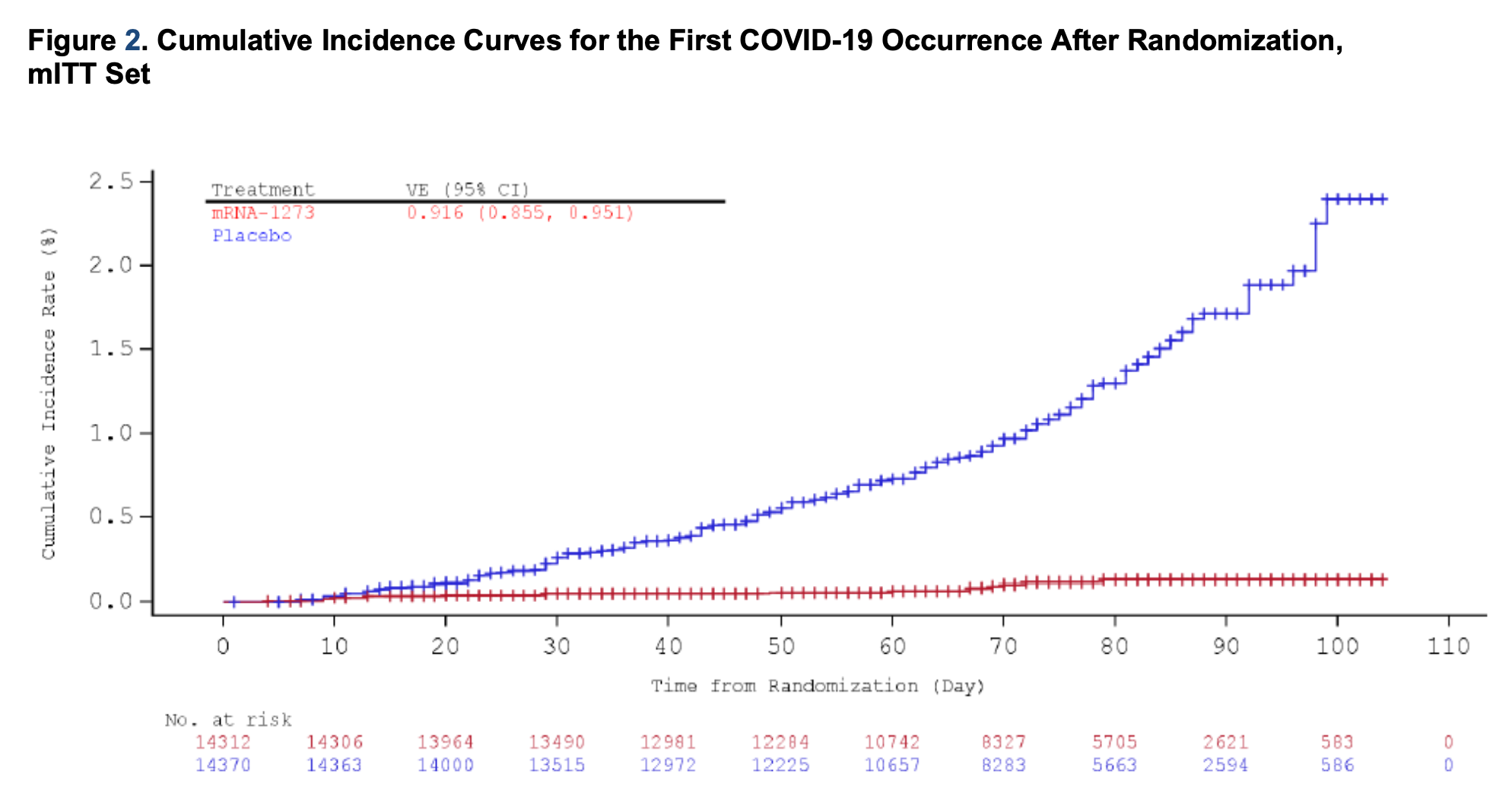

When the Moderna COVID vaccine trial interim results were announced, showing a ~95% vaccine efficacy, I was pretty excited. They announced it in a press release first but I grabbed the FDA submission as soon as I could. Inside, on page 28 (of 54), was a graph that I will never forget:

This is really impressive. This red line is pancake flat, it is the flattest red line in the history of red lines. It is the kind of red line that can withstand any critique wielded against it. The lead statistician looks kind of silly now, like a mediocre professor rambling on -- I mean, they used a modern and very appropriate statistical approach, but in the end they could have gone with the highly underrated Just-Squint-At-It method, and would have been just fine.1

This is a fun little story, but I have noticed that it is too easy to trick yourself into thinking it has some relationship to the way the public consumes data. Ok, fine, maybe we never expected the public to make it to page 28, or get all excited about some graph. People must read something, though, don't they? The press release, maybe?

Trust is all that matters

People do not, in fact, read the press release. This is such an incorrect model that we should probably forget all about it and start from scratch.

Here is how it works. First, log onto YouTube. Apparently there is some new video from Trusted Guy. Cool. Trusted Guy says the Covid vaccine works and you should get it. Or, I don't know, maybe Trusted Guy lies and says it will mutate your genes,2 doesn't matter really, because that's pretty much it. Congratulations! You are now fully informed on this topic.

I did not pick YouTube to be mean: I think this is normal, even healthy. The number of people who have time to do a critical read of anything rounds down to zero. The number that has the expertise needed to form an independent judgment also rounds to zero.

Also, I am talking about everyone here: that time when RFK Jr. called it "the deadliest vaccine ever made," but also articles like this one by Zeynep Tufekci and Michael Mina, where they write

These vaccines are a triumph. In large-scale trials with tens of thousands of participants, both demonstrated around 95 percent efficacy in preventing Covid-19 — a stunning number exceeding our best hopes.

I completely agree, but the average NYTimes reader had seen those names before and just sorta trusted them, right?

The defining event that gets you from "we don't have a vaccine yet" to "we have a fantastic vaccine" isn't the release of a 54-page briefing document, it's a few headlines from a few names you trust. If we're being honest with ourselves here, data people are the same way.

What does this mean for data nerds?

Data people tend to want to believe things like:

I am trustworthy because I conduct my work professionally and carefully apply data analysis methods in an appropriate way.

The hard part of my work is getting clean data and designing the best analysis.3

If I do high quality analysis, people will be interested to see the results.

My colleagues learn valuable insights from my work.4

The truth is that methods and cleaning are often not the bottleneck. Often, the best reason to work on these things is that you care about the craft of research and analysis, and you want to fully grasp the results. That's great, but it won't automatically do anything for your credibility. It won't automatically mean that others will learn what you have learned.

What matters for building credibility? The most obvious is having a good track record. In my last post I said I lost trust in some people during the pandemic, and that they lost my trust basically by being wrong. The hard part being, of course, that data analysts are wrong all the time about stuff, and also that being right for a while doesn't blunt the impact of a single bad mistake.

Aside from that, there is the whole social game we play to decide who we like and want to work with. I am fairly bad at that game and have nothing to add. That's unfortunate, because it is probably the most important part.5

What matters for actual learning to occur as a result of your work? Let's think back to the last time we were in a classroom. Perhaps it was in college. Remember, in college, you pay a lot of money for the privilege to sit in that classroom. Did 90% of your classmates devote real energy to learning (not just racing through assignments but actively working at them)? Did half? Did you?6 Learning isn't passive or easy, and at any given time only a few people will do it.

This lecture is one of my favorite sources on how to write well. It's by Larry McEnerney at UChicago. The basic lesson: like in the classroom, your audience is really small. Most people do not care about your topic, and the few who read it do not care about most things you could write. You must know what things they doubt, and only then can you make effective arguments. And there is always a specific coded language that this narrow audience will use, so you have to be fluent in that too. If you fail at either of these things, nobody will read it.

Know the audience

I feel a little bad for that statistician I said "looks kind of silly." Really, they did all that work only to get "just check out this one graph, the rest is garbage"?

Not exactly. That document is for the FDA, not for random people like me. And the FDA is a brutal audience, so you better believe they will make it to page 28. Oh, you left a single paragraph out? I'm sorry, the Just-Squint-At-It method is decidedly not enough for us, and in fact the entire report is now suspect, so you better revise it if you want us to approve this vaccine.

The statistician is there to communicate with the FDA. End of story. They aren't the one writing the press release, they don't communicate with the public. They know their audience and they do exactly what is needed to convince it.

-

What were these other 53 pages for, anyway? Just for fun? ↩

-

I recently watched a legislative hearing at the state level in Massachusetts where Covid and other vaccines were repeatedly called "gene-altering" by members of the public. You know, Massachusetts has a reputation as a fairly pro-science state. It was painful. ↩

-

School, in particular, tries to convince you that the hard part comes from linear algebra and Other Scary Math Stuff, the constant threat of unmeasured confounding, and That P-value Interpretation Is Wrong Because It's Not The Exact Words I Fed You. ↩

-

Just kidding, I'm not sure anybody thinks this. ↩

-

This is a bummer when you want to correct misinformation. Inevitably the person spreading the misinformation is better at the game than you. If you go head to head here, you will lose! The only way forward is to know with whom you do have credibility, and start there. ↩

-

It is sort of funny that all of us have been in a classroom, but we like to forget the real dynamic as soon as it's us in the teacher role. ↩